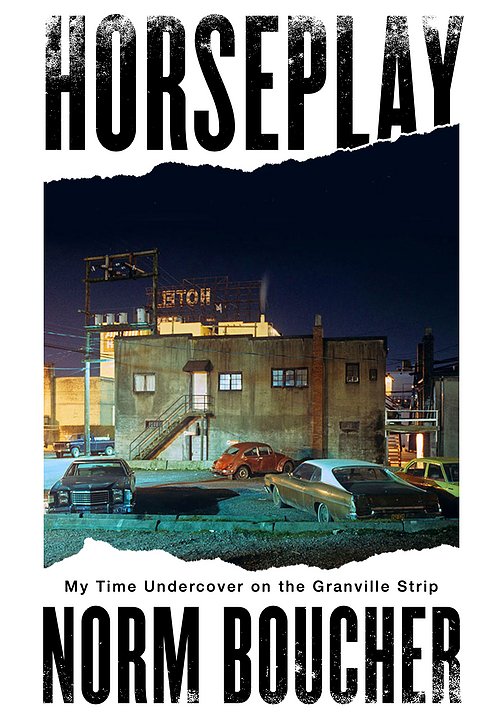

I didn’t have any expectations when I picked out this book. It seemed like it might be an interesting look back at Vancouver in the 1980s. This memoir by former RCMP undercover Staff-Sergeant Norm Boucher, delves into an eight-month undercover heroin operation in Vancouver, specifically around the Granville strip in 1983. Boucher befriends several local heroin users and sets them up in order to gain access to those higher up the drug supply chain. Unfortunately, there is very little that is interesting in this 269-page memoir.

After settling in and trying to gain the trust of his new friends, Boucher gives us some detail on his daily routine, the challenges he faced, a little bit of what he was experiencing emotionally as he tries to sell himself as a heroin user. But there is very little insight, introspection, or self-reflection in this – it’s just the same thing day in and day out. Once we establish a few bits and pieces about the folks he meets and begins to do business with, there is very little else. Does he ever get the bigger guys up the chain? Not really sure – and it hardly seems that some that the operation may have got, weren’t all that far up that chain anyway.

Reading about this time – 1983 – and the drug scene with today’s deeper understanding of the nightmare situation that is occurring on the streets of this city, and applying that to a time 40 years ago, may be a bit unfair, but this book really raises questions about the time, money, and usefulness of such an operation. Boucher doesn’t seem to want to touch on this. He discusses addiction, in a rather small and simplistic way near the end of the book. But he doesn’t challenge his own understanding or the role of the police, public policy and strategy in this situation. He simply tells us what he did, day-to-day. And that gets tedious pretty quickly.

I’m sure he worked from his own notes and had some help with remembering the events that went on during this operation. He talks very little about the investigative team and what they were doing during most of this eight-month indulgence. I’m also rather suspicious of the endless quoted conversations that he had with his various new drug buddies in the beer parlours at the various hotels. He regularly mentions how certain people are suspicious of him – they think he might be a cop. This goes on throughout the book and simply feels like a dramatic device to lead us to believe he was possibly on the verge of having his cover blown. Keep the reader in suspense, somehow, because the basic description of his routine certainly doesn’t.

So this was, even without any expectations one way or another, a disappointing book. While there are bits and pieces that carry you along in places, and this may be enough for some people, it certainly did not have enough to hold me throughout the 269 pages.